Football hooliganism

In contexts of recent tragic event in Athens, where Croatian football fans took place one of the main role, it is important to write (to emphasize) some relevant facts about hooliganism. Football hooliganism and violence has been a global problem for decades.

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a fan is described as “an enthusiastic devotee (as of a sport or a performing art) usually as a spectator,” but football fans, particularly in Europe, usually take the term ‘devoted’ and transform the meaning into something drastically different. From this, there is an entirely different sub-category definition of ‘fan’ that lends itself to a particular group in society; football hooligans. Although much of the research concerned with football hooliganism centres around English football clubs, there are many other fans in Europe, and the rest of the world, that exhibit the same types of behaviour. Football hooliganism, whilst a declining event, is still very much a serious issue in today’s society. Historically, a hooligan is a person who engaged in a type of behaviour that was considered rowdy, or even possibly criminal. Hooliganism was not pre-meditated and violent fights during matches between rival teams were mostly due to the large crowds in small spaces, and the presence of alcohol at games. However, in 19th century England, a change occurred that was categorised as ‘The English Disease.’ In the simplest terms, Braun and Vliegenthart defined football hooliganism as “…organised groups that try to initiate fights with rival groups…” This change, around the 1960-80’s, coined football hooliganism, was a change that presented acts of violence that were planned and related to person engaging in fighting that did not transmit to the specific match itself. This change also saw the formation of rival gangs called firms. Firms were groups of people that came together through their love of a specific team, with the intent to intimidate and physically attack opposing supporters.

Although hooliganism is said to be declining in England, it is still very much alive all across the globe. In the present day, the parametres concerning the act of football hooliganism is far spread, and not always involved with the timing of the game itself. According to Dunning, Murphy, and Williams, there are many situations where hooliganism is evident. For example, there may be hand-to-hand fighting between two people, a group out on the streets, numerous amounts of fans rioting in a stadium, fights between teams travelling to the games, or groups following rival teams after the match has concluded. In an effort to evade police, rival firms may also plan to surprise their counterparts on different days of the week leading up to a specific game. As well as this, there has also been instances where weapons have been used. Although there is clear intent to participate in physical violence, many ‘football hooligans’ state that the intent to harm another is not evident. Leeson, Smith, and Snow state that many fans fight other fans because they believe that this type of behaviour is a part of the game of football, as it always has been.

Football fandom is a well-established social phenomenon and many of its associated behaviours may be considered extreme, or indicative of high levels of group bonding and loyalty. For example, fans travel long distances, invest large amounts of money and time monitoring and participating in their teams’ events and often display visual symbols of allegiance to their team, even lifelong and painful tattoos are not uncommon. Fans are so heavily invested in football that match results have even been associated with circulatory disease death rates in men at both local and national levels.

According to a 2013 report by the BBC, soccer fans are more likely to be violent than fans of any other sport. There are a number of reasons for this, including the fact that soccer is a physical sport that can lead to aggressive behavior and the fact that soccer fans are often divided into rival groups based on their team allegiances. Additionally, alcohol consumption is often involved in soccer violence, as fans drink before and during games in order to work up courage or relieve boredom.

Sports Studies scholars Paul Gow and Joel Rookwood at Liverpool Hope University found in a 2008 study that “Involvement in football violence can be explained in relation to a number of factors, relating to interaction, identity, legitimacy and power. Football violence is also thought to reflect expressions of strong emotional ties to a football team, which may help to reinforce a supporter’s sense of identity.”

Football hooligans often appear to be less interested in the football match than in the associated violence. They often engage in behaviour that risks them being arrested before the match, denied admittance to the stadium, ejected from the stadium during the match or banned from attending future matches.

The study, published in Evolution & Human Behaviour, canvassed 465 Brazilian fans and known hooligans, finding that members of super-fan groups are not particularly dysfunctional outside of football, and that football-related violence is more of an isolated behaviour.

While the findings were linked to Brazilian football fans, the authors believe that they are not only applicable across football fans and other sports-related violence, but to other non-sporting groups, such as religious groups and political extremists.

Although the research does not suggest that either reducing membership to extreme football super groups will necessarily prevent or stop football-related violence, the authors believe that there is potential for clubs to tap into super-fans’ commitment in ways that could have positive effects.

The findings reinforce the research team’s previous work to understand the role of identity fusion in extreme behaviour. They also suggest that fighting extreme behaviour with extreme policing, such as the use of tear gas or military force, is likely counterproductive and will only trigger more violence, driving the most committed fans to step up and ‘defend’ their fellow fans.

Scholars from all across the globe concluded the more they understood the reasons football hooliganism existed, the more they could do to counteract the issue. Many researchers disagree about the exact causes of hooliganism, but all come to an understanding that this type of behaviour is a social phenomenon, engrained with psychological factors. Some of the earliest publications on the causes of football hooliganism were courtesy of Ian Taylor and John. Taylor and Clark both argued that football was a sport that young working-class males identified with. In essence, football hooliganism “…should be interpreted as a kind of working-class resistance movement,” that involved a way for these men to resolve conflict in their own lives. These publications looked at hooliganism as a way for working-class males to blow off steam about the frustrations in other parts of their lives. Both of these researchers were quickly criticised, however, because they lacked any empirical evidence.

From these publications, researchers came to recognise football hooliganism as a ‘figurational sociological phenomenon.’ Figurational sociology is defined as “a structure of mutually-orientated and dependent people,” that have developed a set of values regarded as ‘civilised’ behaviour. These values however, did not integrate into the lower class. These forms of civilisation, namely lack of violence in this case, was not valued in the working class society. Dunning, Murphy and Williams state that the working class also did not have as many forms of excitement as the other classes in society, so the men resorted to fighting as a means for entertainment, disregarding the social normality and expectations of the higher-level social classes around them. These lower-class males developed aggressive behaviours because of their willingness to fight and their adoration of masculine leaders. Both of these factors were the criteria for becoming part of a group. From expressing their behaviours in a lower-class, males were often rewarded and received ‘pleasurable’ feelings, rather than anxiety about violent occurrences. The more that these men were rewarded for violent behaviours, and the more they joined the ranks of a sought-after ‘firm,’ the more the responded to situations with violence.

Although many scholars still discuss figurational sociology in sport today, many of these theories have been disproved because these types of behaviour and civilisation values are not exhibited in other football hooliganism incidents around the world. Ek noted that in West Germany, there was an increase in football hooliganism from the upper and middle class. As well as this, other countries football hooliganism patterns suggest that differences are due to religious beliefs, geographic location, generational variance, and race, rather than a difference in social class.

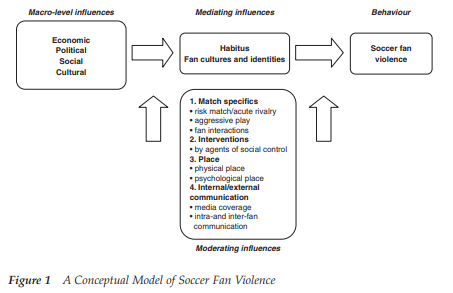

Drawing from all the theories mentioned, Spaaij and Anderson adopted the position that football hooliganism is a form of collective violence that shapes social actions based on social identification. As defined by the World Health Organization, collective violence is “the instrumental use of violence by people who identify themselves as members of a group…against another group or set of individuals, in order to achieve political, economic, or social objectives.” From collective violence, Spaaij and Anderson displayed a conceptual model of soccer fan violence that involved macro-level influences such as match specifics, interventions, place, and communication, and mediating influences such as second nature and fan identity. These three influences, as shown in the diagram below, lead to the type of behaviour seen as football violence, or hooliganism.

The first of these influences relate at a macro-level and have been explained by Braun and Vliegenthart, concerning economic, political, social, and cultural features. Factors such as lower working-class individuals, a large crowd, alcohol, rivalries between teams, and the intensity of the match and between the players combine to form a perfect scenario where crowds can start to become violent, and engage in behaviours concurrent with the definition of football hooliganism.

From the combinations, comes a number of other influences that are far more psychological. “Mediating influences explain how cause translates into effect, while moderating influences are those factors which affect the intensity of direction of effects”. Individuals identify with a collective, in this case a firm, and then learn behaviours that are directed at “…the object of their contention,” such as a rival firm. Each individual has inherent differences and diverse personal experiences, but their second nature is the ability to act the same in similar situations as others in the group. From this, the members of the group can identify with each other, and share common interests, as is the case for fan violence. The identity that comes with being a member of a firm is the result of economic, political, social, and cultural differences that intertwine together to make one collective group with a common goal: dominance over a rival firm.

Although these mediating influences explain how cause turns into effect, moderating influences explain why some incidents of football hooliganism are more intense than others. According to Bairner, the hooligan experience is based on excitement and arousal, and involve individuals who want to engage in thrilling behaviours. Although many fights occur at rivalry games, and between firms that have well-known rivalries, these fights do not always occur because of their distaste for the other firm, rather from the excitement, or the hype of fighting against a well sought-after rival. Most of society views hooliganism as mindless fighting, but it is rather a very rational and organised form of social control within a sub-culture. The media also plays an influence in moderating forms of fan violence in football, as the more masculine the headlines seem to the public, the more firms want to start fighting to show their own dominance.

Taylor, Clark, and Braun and Vliegenthart recognised and labelled key macro-level influences in regards to football violence. These influences described first and foremost from crowd size and increasing rivalries between teams, initiate hooligan behaviour in football for working-class males and their need to release the frustrations of their everyday life. Combined with the need to identify with a group, and the notion of dominance and masculinity, these influences highlight the behaviours exhibited by fans that leaders to football hooliganism, or pre-meditated violent attacks on opposing teams.

Violence is not rare in today’s society, nor is it rare to continuously see all types of violence occur at sporting events and games throughout the world. Violence at these types of events are social phenomenons, with football hooliganism paving the way. Hooligans exhibit behaviours that cannot be broken down and labelled by one specific cause, but always display the need for social identity, masculinity, excitement, and dominance over others. Although declining in many parts of the world, football hooliganism is still a very serious issue in sport’s violence, and the work and research of the scholars mentioned in this paper may be a factor to consider when looking at aggressive behaviour in other contact sports.

LITERATURE:

Adam John, Why Soccer Fans are Violent – (thesportsground.com), 2023.

Brewin, Ed. Hooliganism in England: The Enduring Cultural Legacy of Football Violence. ESPN FC, February 2015.

Clark, John. Football Hooliganism and the Skinheads. Birmingham: University of Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, 1973.

Kirkup, W., & Merrick, D. W. (2003). A matter of life and death: Population mortality and football results. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57(6), 429-432.

Newson, M. (2019). Football, fan violence, and identity fusion. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(4), 431–444.

Newson, M., Bortolini, T., Buhrmester, M., da Silva, S., Acquino, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2018). Brazil’s Football Warriors: Social bonding and inter-group violence Evolution and Human Behavior.

Paul Gow and Joel Rookwood (2008) Doing it for the team – examining the causes of contemporary English football hooliganism. Journal of Qualitative Research in Sports Studies, 2, 1, 71-82.

Spaaij, Ramon & Anderson, Alastair. (2010). Soccer Fan Violence: A Holistic Approach A Reply to Braun and Vliegenthart. International Sociology , 561-579.

Taylor, Ian. “Football Mad: A Speculative Sociology of Football Hooliganism,” in Dunning, Eric. The Sociology of Sport: A Selection of Readings. London: Frank Cass, 1971. 352-77.